On February 1, 1984, two weeks before her 50th birthday, Audre Lorde’s oncologist informs her that she has liver cancer, metastasized from the breast cancer for which she’d had a mastectomy 6 years earlier, in the autumn of 1978. She had documented her experience receiving a positive diagnosis, opting into, and recovering from her mastectomy in her 1980 work, The Cancer Journals. In that work, she writes about the power attained in living with an awareness of one’s mortality: “Once I accept the existence of dying, as a life process, who can ever have power over me again?”

Still, this reworking of death into a life process did not blunt the shock and pain of cancer’s return. She refused the standard treatments—biopsy, surgery, radiation, chemotherapy. This was partly a rational decision based on information from her breast surgeon that, at best, these treatments only stood to extend her life by a year or two, while being carcinogenic in and of themselves. Part of Lorde’s acceptance of death as a life process meant prioritizing quality of life over sheer longevity. But it was also part denial, desire for the spots on her CAT scan to be benign, “some little aberrant joke between my liver and the universe.” Yet she acknowledged she “mustn’t let my unwillingness to accept this diagnosis interfere with getting help.”

Lorde’s investment in her own bodily autonomy as a cancer patient and her decision to refuse standard treatment was met by hostility from her doctors in New York:

I have dealt with doctors who laid the most bone-crushing pressures upon me, to have biopsies for instance. They threaten you not only with the fact that you might die but also for being stupid and emotional. They withdrawn their support by claiming I won’t be responsible for this. It is frightening. The only answer is to learn to withstand certain pressures in our lives by recognizing the other forms of pressure we are always under. […] We need to develop a larger stance on our bodies and all areas of our lives so we may learn to say no and defend our own interests.

In May, 1984, Lorde departed New York for a teaching trip in Berlin where she hoped to learn more about the Afro-German diaspora. During this trip, feminist sociologist and filmmaker Dagmar Schultz introduced Lorde to a Berlin-based anthroposophic medical doctor, Michaela Rosenberg, who confirmed her New York doctors’ diagnosis of liver metastasis.

Unlike the Western medical doctors in New York, Lorde felt that she could trust Dr. Rosenberg because Rosenberg respected Lorde’s decisions about her body, even when disagreeing with them. Lorde decided to try a naturopathic chemotherapy treatment of Iscador injections, an aqueous extract of mistletoe leaves, stems, and berries that contains bioactive compounds believed to stimulate the immune system, inhibit tumor growth, and improve quality of life for cancer patients (with mixed empirical support). (Rudolph Steiner, creator of anthroposophy, believed mistletoe, as a parasite, might be treat the ‘parasite’ of cancer, following homeopathy-founder Samuel Hahnemann’s “like cures like” principle. It’s thought to warm the body’s immune system, often inducing low-grade fever, making it less hospitable to cancer, a disease of excess coldness.)

Mistletoe therapy is typically offered as an adjuvant to support the patient’s response to traditional chemotherapy or radiation, although this was the only ‘chemotherapy’ treatment Lorde underwent. Iscador appealed to Lorde because it purports to heal via the body’s own powers of self-defense and regeneration by boosting the immune system—a sharp contrast to the cytotoxic and militarily-derived compounds used in standard chemotherapy treatments.

The fantasy of self-healing was central to Lorde’s courageousness in the face of cancer. During her first bout with cancer in the late-1970s, Lorde took solace in controversial psycho-oncologist O. Carl Simonton’s Getting Well Again (1978), which stresses patients must take an active role in their own healing, going so far as to (erroneously) claim cancer can be treated through relaxation and visualization techniques and blaming remission on anxiety & depression. In The Cancer Journals, she wrote that Getting Well Again “has been really helpful to me, even though his smugness infuriates me sometimes. The visualizations and deep relaxing techniques that I learned from it help make me a less anxious person.” She offers up the The Cancer Journals in hope that “these words underline the possibilities of self-healing” for all women.

Across the end of 1984 and the first part of 1985, Lorde “removed the question of cancer from my consciousness beyond my regular Iscador treatments, my meager diet, and my lessened energies.” Cancer was a constant navigated in the background, but not a central event her life. In November, 1985, she received bad news via another CAT scan, which showed the initial liver tumor spreading and a second emerging. Even so, she refused to accept these tumors as malignant, although more of her was coming around to acknowledging that “the axe is falling.” But friction with her doctors made this all the more difficult: “they’re treating my resistance to their diagnosis as a personal affront. But it’s my body and my life and the goddess knows I’m paying enough for all this, I ought to have a say,” she wrote in December, 1985.

In response to the worsening prognosis, in December, 1895, Lorde underwent in-patient care at the Lukas Klinik, an anthroposophic hospital in Arlesheim, Switzerland specializing in holistic cancer care, established in 1921 by Ita Wegman and Rudolf Steiner, the pioneers of anthroposophic medicine. “I think they will be able to find out what is really wrong with me at the Lukas Klinik, and if they say these growths of my liver are malignant, then I will accept that I have cancer of the liver,” she wrote on November 21, 1985. “There is absolutely nothing they can do for me at Sloane Kettering except cut me open and then sew me back up with their condemnations inside me,” she concludes in the same journal entry.

Anthroposophic Medicine emerged in response to the reductionism taking hold in Western medicine in the early-20th century. Western medicine tends to explain life, health, and disease by reference to underlying physico-chemical processes at the cellular and molecular levels. Anthroposophic medicine treats these physico-chemical processes as the material conditions from which higher-order properties of being (life, soul & spirit) emerge. These higher-order domains have their own laws, and cannot simply be reduced down to molecular activity in the material body. Vitality and energy, so central to the experience of inhabiting a body, cannot just be reduced to the body’s physico-chemical materiality.

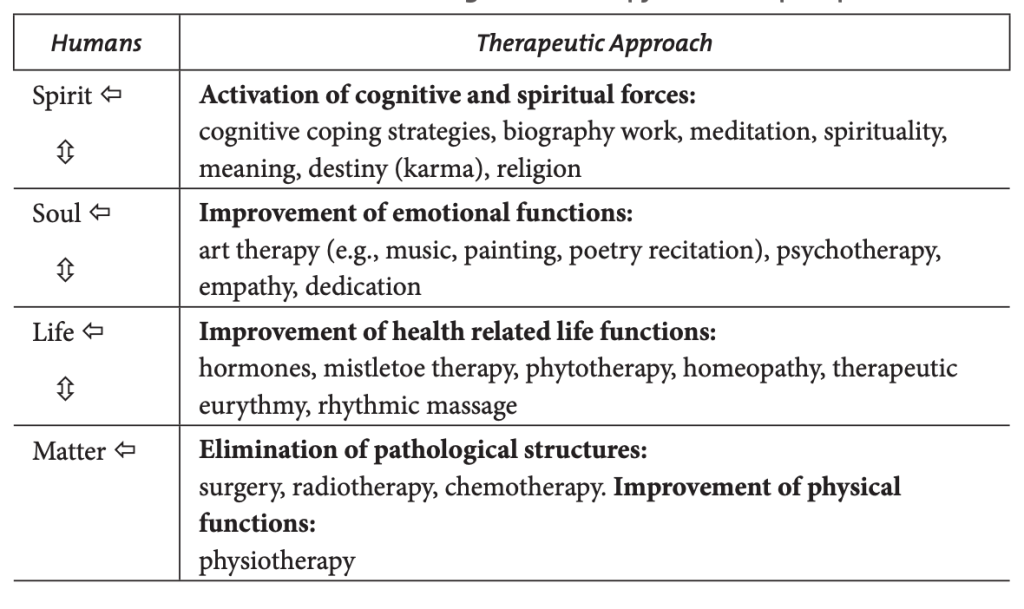

As a medical practice, anthroposophic medicine turns to integrative practices to treat the whole of the human, not just targeting the molecular bases of illness in a bottom-up manner. From the anthroposophic perspective, illness results from disharmonious interactions between physical, life, soul, and spirit organizations of the individual and can be top-down as well. The table below, from Heusser & Kienle (2014), illustrates the integrative approach to health taken by anthroposophic medical practitioners.

Material life tends toward entropy, but living beings use vital energy to organize and regenerate the body, maintaining low entropy within the living system. Lorde found this way of thinking compelling, allowing for the conceptualization of death alongside life, rather than sheerly its negation. She wrote from the Lukas Klinik, “As a living creature I am part of two kinds of forces—growth and decay, sprouting and withering, living and dying, and at any given moment of our lives, each one of us is actively located somewhere along a continuum between these two forces.” Unlike in the U.S., Lorde feels the anthroposophists are able to speak about cancer with a calm directness that does not shy away from the idea or reality of disease and dying.

At Lukas Klinik, Lorde’s dosage of Iscador therapy was upped to its maximum dosage. She undergoes massages, oil dispersion baths, and hot yarrow liver poultice. She also participated in art therapy and eurythmy, a kind of expressive dance therapy redolent of modern dance made up of rhythmical body movements and controlled breathing, based upon vowel and consonant sounds. In their Fundamentals of Therapy, Steiner and Wegman write that these special movements “react on the diseased organs. We observe how the outwardly executed movement is continued inward with a health-giving influence into the organs, the moving gesture is exactly adapted to a diseased organ.” Movements are embodied translations of the spiritual force of music. Lorde notes the statue of Steiner outside Lukas Klinik, “one arm upraised in the eurythmic position for the vowel i wish is considered in all languages to be the sound representing the affirmation of self in living,” the vowel out of which Lorde the biomythographer weaved her art.

Lorde found the Klinik’s emphasis on active meditation especially helpful as a means of tapping into self-control within a larger process of disease that too often leaves patients feeling helpless. Meditation involved focusing on small objects and small acts as circumscribed spaces of control, e.g. thinking exclusively of a small object like a paperclip for five minutes every day for a month; performing a small action at the same time of day to practice patience. This focus on locality was intended to ward of catastrophizing, uncontrollable feelings, and the closing off of the self to the world.

But Lorde also chaffed at the Klinik’s strictures and overwhelming whiteness, and found the iciness of Swiss winter at times unbearably estranging. She found the clinicians to be dogmatic in their anthroposophic beliefs, as if they were unable to accept the spiritual aspect of embodiment without Steiner’s rigidity. Despite anthoposophy’s emphasis on the spiritual properties of color, Lorde found in the scenery and people an “extraordinary blandness.” A gauziness permeated the atmosphere—”very lovely. Just don’t be different. It’s bad for you.” Lorde encountered racism from other guests, and the ambient suffering of neighbors dying in adjacent rooms. As the visit stretched on toward Christmas, Lorde reports her “heart aches from strangeness.”

On December 23, 1985, Lukas Klinik’s anthroposophic doctors confirmed the malignancies of Lorde’s liver tumors, eliminating the last remnant of doubt to which she could cling. The estrangement she’d felt the previous days permeated her body, the longtime locus of wisdom she’d come to rely upon: “The question is what do I do now? Listen to my body, of course, but the messages get dimmer and dimmer.” On Christmas Eve, she writes that she feels “trapped on a lonely star.” She wonders, “Does one simply get tired of living?”

On Christmas, Lorde’s heretofore tempered frustrations with the Klinik erupt. The front desk won’t let her place calls to her partner Frances or her children. She excoriates the Klinik’s hallowed cloistering of its patients: “Nobody here wants to pierce this fragile, delicate bubble that is the best of all possible worlds, they believe. So frighteningly insular. Don’t they know good things get better by opening them up to others, giving and taking and changing? Most people here seem to feel that rigidity is a bona fide pathway to peace, and every fibre of me rebels against that.” But that night, Lorde is blessed by a full moon, which diffuses through her dreams and then at 4:30am summons her out onto the terrace, and under its clarity of light she “prayed for us all, prayed for the strength for all of us who must weather this time ahead with me.”

On New Year’s Day, Lorde and Frances hike to the top of a mountain to see the Dornach ruins. She has recommitted herself to love and her loving circle, “the most potent and lasting force in life, even if certainly not the fastest.” She recalls her mother saying “Whatever you do on New Year’s Day you will do all year round,” and hopes that this reinvigorating use of her body will be how she spends 1986.

Lorde spends the rest of winter and spring in St. Croix absorbing heat into her bones. In anthroposophic medicine, cancer is a “cold” disease. Mistletoe’s supposed internalization of light and warmth, for Steiner and his followers, gives it its cancer curative properties. For Lorde, Arlesheim proves to be a blast of iciness that is unpleasant, if necessary for her commitment to regimens for survival. It is the heat of St. Croix that spiritually restores her.

One year following her arrival at Arlesheim, Lorde writes, “It is exactly one year since I went to Switzerland and found the air cold and still. Yet what I found at the Lukas Klinik has helped me save my life.” By “save my life,” Lorde doesn’t simply mean delaying the progress of cancer, although she does credit her work with the slight diminishment of her liver tumors in summer 1896. More to the point, the exercises she learned from anthroposophy—e.g. active meditation, eurythmy—and the Iscador injections allowed her to wrest bodily autonomy from the overwhelm of disease and doctors.

“Making it really means doing it our way for as long as possible,” and making it was not possible for Lorde under a regime of Western medicine she felt constantly dismissed her concerns, infantilized her, insisting that “I really did not have any other sensible choice” than to do they was prescribed for her. At the same time, bodily autonomy did not mean, for Lorde, absolute surety in her own opinions, or absolute faith in the healing power of alternative medicine. “Living with cancer has forced me to consciously jettison the myth of omnipotence, of believing—or loosely asserting—that I can do anything, along with any dangerous illusion of immortality,” she writes at the end of A Burst of Light, in 1987. Bodily autonomy means living awake to the indeterminacies of the sick body.

Ultimately, what Lorde took from anthroposophic medicine is an attunement to the body and its needs without hysteria or catastrophe, tools for practical control over her embodiment instead of fantasies of immortality. She made it syncretic with her Africanist view of life, oriented to experience as something to be lived, not as a problem to be solved. The result is what Lorde called “the burst of light—that inescapable knowledge, in the bone, of my own physical limitations,” a knowledge braided into the fabric of everyday life, which “makes the particulars of what is coming seem less important.” After all, Lorde comes to an understanding of the good life amidst terminal cancer which means “time over which I maintain some relative measure of control,” to “stretch as far as I can go and relish what is satisfying rather than what is sad,” and to build “a strong and elegant pathway toward transition” from this life to what comes after.

Leave a comment