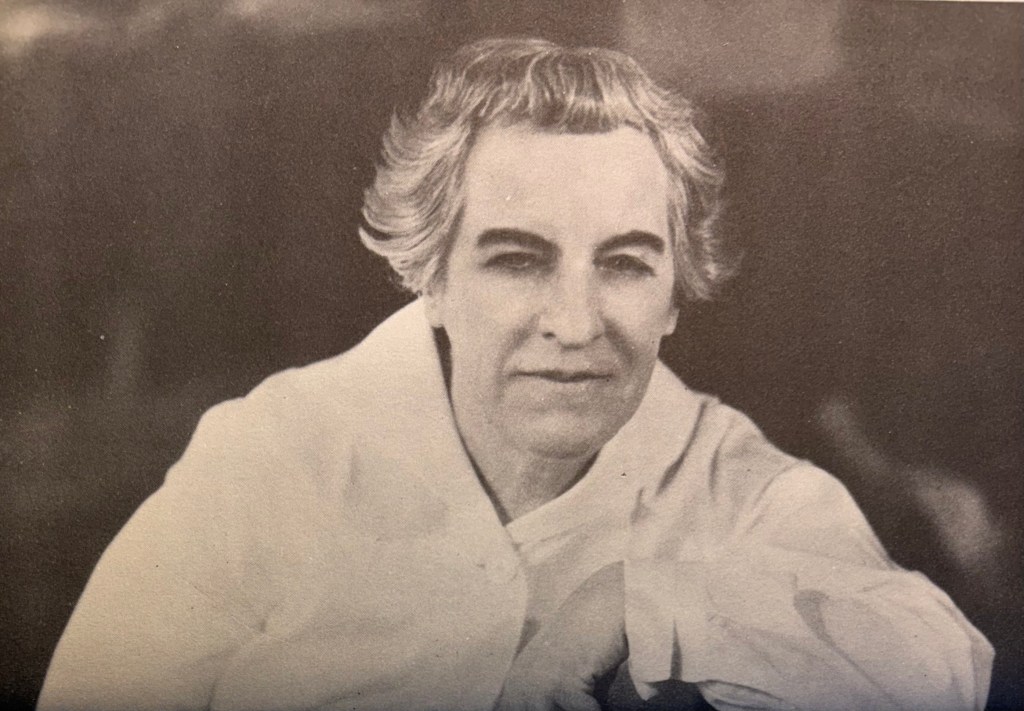

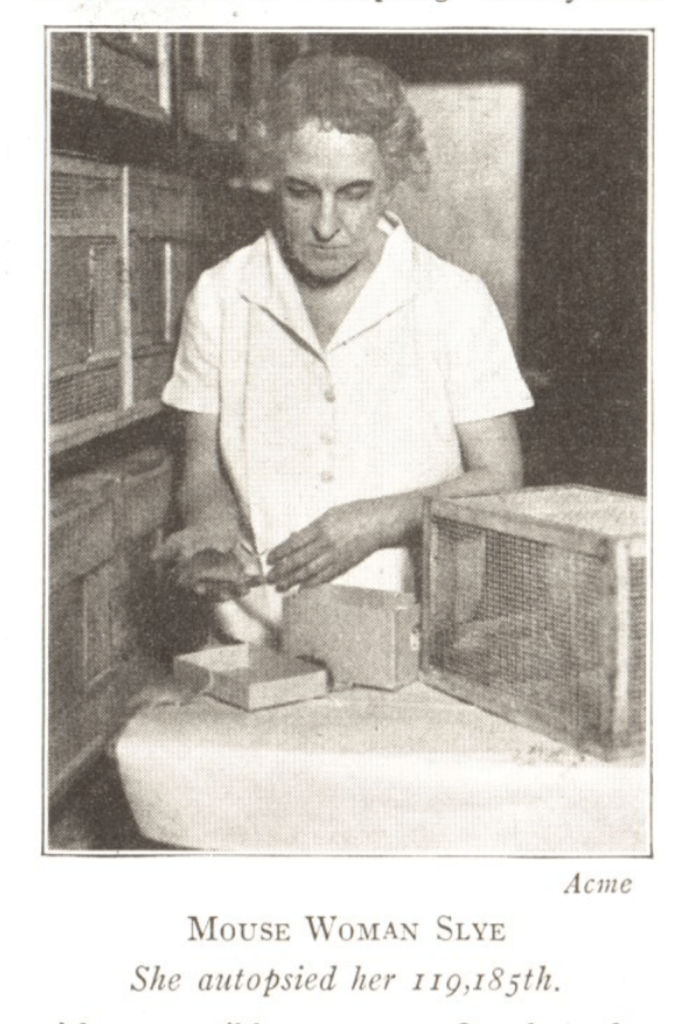

Maud Slye the “Mouse Woman”

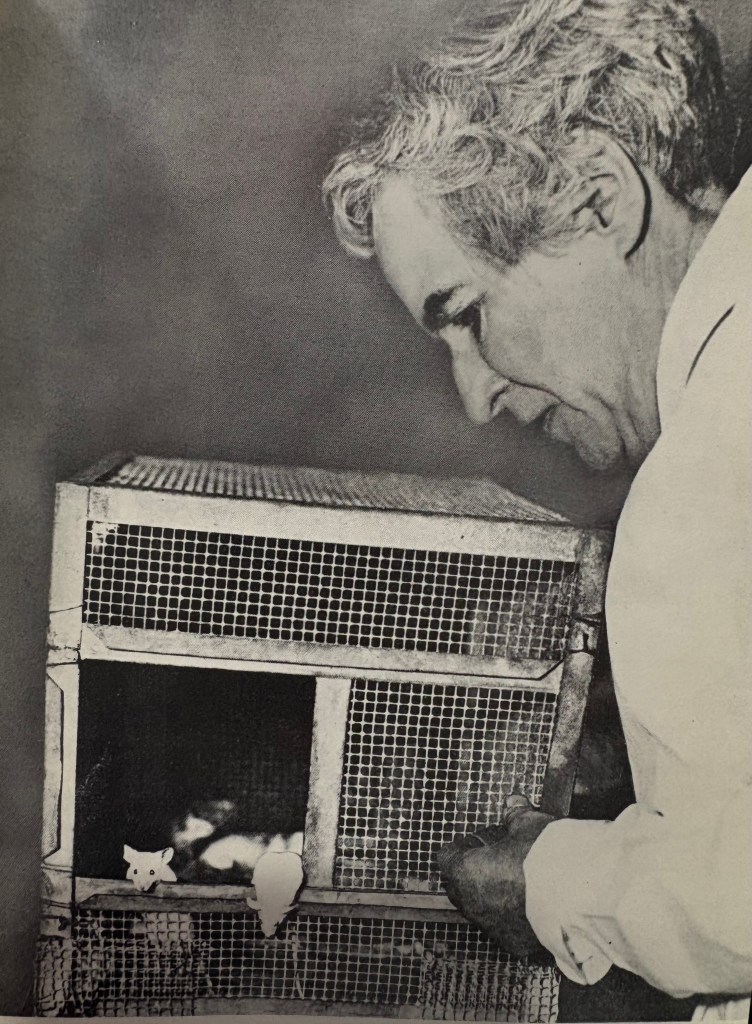

Maud Slye is a complicated figure in women’s history. She was the first female cancer researcher, and her research was crucial in establishing genetics as a central area of cancer research. She and her cancerous mice were the most visible advocates of the position that genetics underwrite cancer, presciently arguing against the common theory that cancer was parasitic in origin and not heritable, earning her the moniker of “Mouse Lady” in the press. In her tireless inquiry into cancer causation, Slye helped to invent the field of modern day animal model research: she pioneered the use of genetically uniform mouse models resulting in the longest and most extensive breeding program ever carried out by a single researcher at the time. In 1940, the Women’s Centennial Congress recognized her, along with Margaret Mead and other major female scientists, as a beacon of the progress women had made over the past century.

At the same time, Slye, like many feminist and scientific utopians of the era, was one of the most vocal proponents for the eugenic control of cancer. She compared herself to Karl Pearson, and made headlines with claims like the following given to Time in 1937: “I breed out breast cancers. I don’t think we should feel so hopeless about breeding out other types. Only romance stops us.”

Slye’s eugenicist views were based on her controversial and incorrect opinion that susceptibility to cancer is caused by a single recessive gene, and conversely that absolute cancer immunity could be selected for—meaning that cancer could be bred out of the human race through selective mating. Although Slye’s eugenics seemingly lacked the racialist element of Pearson and most other eugenicists, her contemporaries within the world of cancer research sharply criticized her public messaging for offering false hope broadly, while inspiring shame and fear in cancer patients and their children.

Self-denial underwrote much of Slye’s success. Early in her career, with only a paltry stipend to support herself and her research, she would often forgo meals to purchase food for her mice instead. For many years, she spent all her waking hours in her lab with no one but her mice to keep her company. She went 26 years without a vacation, fearing what would happen without her there to oversee lab operations. She also never married, nor (in available records and histories) had any substantial romantic life aside from a vague affair with an artist early in her life.

Accounts of Slye’s life, contemporary and retrospective, often detect something perverse beneath this intensive self-denail. Colleagues on campus and fellow cancer researchers saw her as an eccentric, preferring the company of mice to people. These impressions were fanned by Slye’s eugenicist critiques against letting romance drive human reproduction (e.g. “only romance stops us” breeding immunity to cancer), which some contemporaries lamented as an attack on the family. Histories of her later life, too, paint a bleak picture of a sexless spinster fading into obsolescence: “She never married and spent her retirement reviewing data from her research.”

Maud Slye the Queer Poet

But Maud Slye was also a poet, and the two thick volumes of poetry she published in her lifetime—Songs and Solaces (1934) and I in the Wind (1936)—attest to her burning romantic passions, keen sensuality, and pained relationship to desire. These poems are strikingly explicit in their homoeroticism, at an historical moment in which a recognizably lesbian literature and culture was just beginning to emerge, and primarily from avant-garde corners (the first explicitly lesbian American poetry collection is often dated to 1923, and the first lesbian novel to 1928). Slye’s poetry thus marks an important contribution to the Pre-Stonewall queer literary canon.

Slye’s directness in dealing with lesbian desire is evidence, for example, in “Why Have You Decked Your Hair?” The poem is addressed to a “little bride” ornamented for her groom-to-be. It stages a queer triangulation of desire, in which the female speaker addresses her beloved who is about to marry her husband. The poem aligns marital heterosexuality with artifice (heart “decked…so guilefully”) and homoerotics with natural truth (“just your naked heart/For me”), upending prevailing homophobic associations of homosexuality with the unnatural. Instead, husband’s desires are grounded in the woman’s transformation into an ornament; the speaker’s desires derive from the woman herself.

Why have you decked your hair

O little bride?

The silken gold of your young hair

Needs naught beside.

Why have you garbed your grace

In subtle dress?

It needs nor line nor lace

Your loveliness.

Why have you decked your heart

So guilefully?

There needs but just your naked heart

For me.

In a later poem, Slye renders lesbian erotics not just as natural, but as a means of being “impregnat[ed]” by nature herself.

I have been intimate with nature all the morning

…

Her blest lips have kissed me

Her full breasts have held my head,

Her arms have folded me—

Her bower was my sanctuary

And her touch upon my life

Impregnates me

With dreams—the children of her realm!

[From “Symphony in E-flat Major”]

The triangular desire of “Why Have You Decked Your Hair?”—the speaker eroticizing a woman entering the cloister of marriage—repeats across several of Slye’s sapphic poems. It’s a scene of queer exclusion transformed into surplus sexuality (surplus to the enclosed heterosexual binary). This is no more evident than in her poem, “This Passionate Serai,” wherein the speaker becomes aroused from dawning a sari weaved by “some Indian girl/Wanting her lover!” The poem is breathless in its orientalist erotics, describing to the “ecstasy of hot desire” conveyed to the speaker from the Indian girl’s “ripe breasts and ready belly.” It attests to the queer, albeit it racist, transitivity of desire, unable to be contained by dyad, heteroreproductivity, or continent.

“This Passionate Serai”

This passionate serai

Made by some Indian girl

Wanting her lover!

Woven glowing depths of crimson

Shot through with patterned silks of gold

And delicate lines of blue like mid-day skies—

Even as her driven passion of desire

Was shot with who shall say what mystery threads of love!

I throw it over me to rest,

Thinking that I shall sleep,

But all that ecstasy of hot desire

Wherewith she wove this drapery and embroidered it

Stirs me away from sleep or any rest

Into the land and in the sunshine where this thing was made.

Passionate red serai

Broidered in gold

And shot with blue of eastern skies—

This slender Indian girl

With great dark eyes that lighted all her face,

With slender limbs browned by her southern skies,

With her ripe breasts and ready belly

And all her passion for her lover—

She stands here by the couch where I would sleep

And rouses me beyond the need of rest

Remembering her!

Such poems transform the irreality of the speaker’s homoerotic desires in comparison to the socially sanctioned intimacies of marriage and reproduction into an unwieldy queer transitivity. They are one solution to the problem of forbidden desire Slye’s poetry circles about again and again. This is a problem allegorized in “Puberty Called Me Yesterday,” which depicts the sexual desires issued by puberty as an infant “famished foundling” “whose food I find not.” Contrary to the embrace of desire’s transitivity evident in other poems, this poem, exasperated, asks for a release from sexuality: “Puberty call no more!”

“Puberty Called Me Yesterday”

Puberty called me yesterday

But the bell has stopt

And sounds no more.

What should I do with this wan babe

That cries within my arms?

Seeking an air to breathe

The world can offer not,

Seeking a food

I cannot find within the forests where I wander

Bearing this wailing child.

…

Where can I lay this famished foundling?

Whose food I find not,

Whose shelter that can house it from the storm

I do not reach.

Puberty call no more!

Sly’s depiction of desire as a foundling resonates with queer historian Christopher Nealon’s term for queer writers in the pre-Stonewall moment struggling toward a collective belonging denied to them in the immediacy of the present. Nealon writes, “This relationship, which I call ‘foundling,’ entails imagining, on one hand, an exile from sanctioned experience, most often rendered as the experience of participation in family life and the life of communities and, on the other, a reunion with some ‘people’ or sodality who redeem this exile and surpass the painful limitations of the original ‘home.’” Sodality arrives through a search for non-biological kinship in history and in a kind of diaspora of far flung, remote, but imaginatively available others. Thus, Nealon’s language of foundling: “the word allegorized a movement between solitary exile and collective experience,” albeit in a moment in which this collective experience is not easily or immediately at hand.

We can see Slye attempting to house her foundling desire in an imagined community of dissident women across history. “O All the Exotic Women That Have Ever Lived” celebrates the erotic sensuality of women past, a sensuality that has throughout history led to “men’s undoing.” This imagined rupture of heterosexuality from the inside “intoxicates” the speaker all the more.

“O All the Exotic Women That Have Ever Lived”

O all the exotic women that have ever lived

Seem folded in the heart of this camellia

That so intoxicates my sense!

Their rounded breasts as waxen as these petals,

The beauty of their faces not to harbor thoughts,

But only to enchant with line and color,

Their treasured limbs only to be possessed

To men’s undoing.

O all you dead exotic waxen women

For whom men gave their souls,

Your perfume wafted down the ages,

Incarnate in this pallid white camellia

That so intoxicates my sense!

Nonetheless, desire in the present remains painful, marked by estrangement and exclusion. “Give Me a Square of Ice” addresses the burden of the romantic outcast’s desire.

Give me a square of ice,

That I may lay it on my breast,

For any heart that beats too high

Is outcast to the rest.

Give me a bandage for my eyes

For looks that see too far

Trouble the still horizon

Of things that are.

The outcast’s desires are redeemed in the past and the future, but rarely the now. In the above poem, the speaker sees too far into the future, toward a freer arrangement of sexuality, but this prophetic vision “trouble[s] the still horizon” of “the things are are” in the restrictive present. Repeated across Slye’s poems are a sense that only things that have slipped from the here and now can be truly available for communion, made literal in poetry addressed to dead lovers.

“Now You Are Dead”

Now you are dead—

And in imagination I can lie with you,

Beside your narrow grave,

Who could not lie with you in life.

The sense of estrangement, scorn, and impossibility that mark the relation between speaker and beloved object in Slye’s romantic poetry testifies to the social prohibitions on female homoeroticism pre-Stonewall, as well as the transience of homoerotic affairs, kept private or sacrificed to respectable heterosexual marriage. Yet persisting amidst the pain of holding impossible desires is a defiant queer gaze that refuses “to change”—even if it means forgoing the eternal bliss of heaven. This is the upshot of “If I could Lean My Head Against Your Breast”:

If I could lean my head against your breast,

And feel your hand caress my hair, as once it did,

And all the magic in your tender fingers hid

Could bring me rest!

…

Though some high god should proffer me the bliss

That lies within the scope of all eternity,

Nothing immortal gifts would bring could challenge me

To change for this!

Slye’s poetry resists salvational thinking—Oh let me be delivered to a more hospitable time! Rather, its erotics are deeply embedded in moments of solidarity that emerge from within the storm. Defiance and resilience are what join Slye’s speaker to “the everlasting stress of time” composed of so many others who have carried impossible desires “like a flaming torch/Burnt with desire for what I can but strive to reach,” as Slye puts it in another poem. The queerness of desire across her poems lies in its unwieldy transitivity, its scorching leaping across sanctioned forms that would contain it (to marriage, reproduction, the historical present).

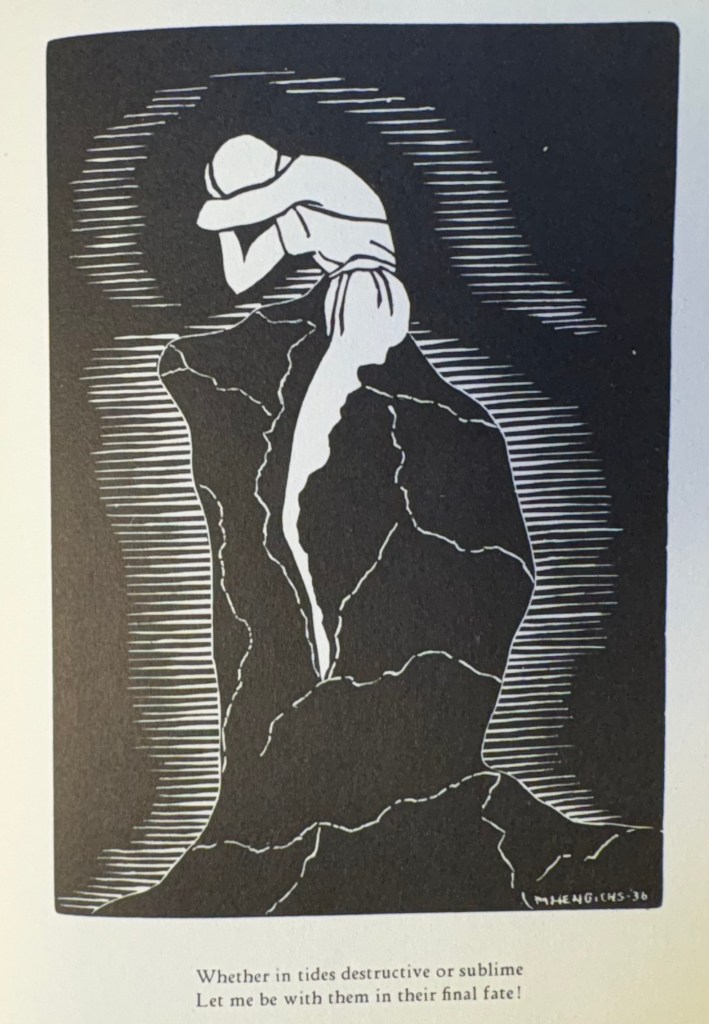

Thus, Slye concludes her final book of poetry with an embrace of the “foundling” status of herself and her desires as a wayward force that “integrates” her into the hauntological undead of queer history:

“Postlude: I Do Not Ask for a Place”

I do not ask for a place

Only the will to do and power to do,

Craving not even any smile from you

Only a block of stone whereon to trace

The pattern I have wrought

Out of my life, out of the soul of me,

Reaching in gladness toward the things that be,

Fixing in rock the beauties I have sought;

…

I build no sheltering tent

Nor cover for protection or retreat

I only ask my carven stone may meet

Whatever storms whatever peace is sent;

So to be integrate

Within the everlasting stress of time;

Whether in tides destructive or sublime

Let me be with them in their final fate!

***

To my knowledge, Slye’s personal papers do not survive in the archive, so there’s no way of ascertaining how she might have identified autobiographically, or what shape her lived sexuality took. Yet her poetry testifies to a keen understanding of being an erotic outcast. That said, if any wayward readers happen to come across this post who have a greater knowledge of Slye’s autobiography, please reach out!

In light of discovering Slye’s homoerotic poems, I have been thinking about her problematic eugenic commitments as complicatedly queer. Her poetry depicts heterosexual marriage as an always already tainted affair given its involvement in a patriarchal order. Thus, her ability to brush off (straight) romance as an impediment to flourishing. Her proposal amounts to something like rationalizing heterosexual breeding, while allowing the real unwieldiness of romance to take less biological issue. This is a topic I’m exploring in a longer in progress article on Slye. More to come.

Further Reading

J.J. McCoy, 1977. The Cancer Lady: Maud Slye and Her Hereditary Studies. Thomas Nelson Inc.

Christopher Nealon. 2001. Foundlings: Lesbian and Gay Historical Emotion Before Stonewall. Duke.

Illustrations are original to Slye’s I in the Wind.

Leave a comment